Reviewing All the Muscles You Have Studied So Far Which Ones Allow You to Look Up at the Ceiling

Learning Objectives

- Identify the axial muscles of the face up, caput, and cervix

- Place the movement and role of the confront, head, and neck muscles

The skeletal muscles are divided intoaxial (muscles of the body and caput) andappendicular (muscles of the arms and legs) categories. This system reflects the bones of the skeleton system, which are likewise arranged in this style. The centric muscles are grouped based on location, function, or both. Some of the axial muscles may seem to blur the boundaries considering they cross over to the appendicular skeleton. The kickoff group of the axial muscles you will review includes the muscles of the head and neck, so you volition review the muscles of the vertebral cavalcade, and finally yous will review the oblique and rectus muscles.

Muscles That Create Facial Expression

The origins of the muscles of facial expression are on the surface of the skull (remember, the origin of a muscle does non motion). The insertions of these muscles have fibers intertwined with connective tissue and the dermis of the skin. Considering the muscles insert in the skin rather than on bone, when they contract, the peel moves to create facial expression (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Muscles of Facial Expression. Many of the muscles of facial expression insert into the skin surrounding the eyelids, nose and oral cavity, producing facial expressions by moving the skin rather than basic.

Theorbicularis oris is a circular muscle that moves the lips, and theorbicularis oculi is a circular muscle that closes the heart. Theoccipitofrontalis muscle moves upwardly the scalp and eyebrows. The muscle has a frontal abdomen and an occipital (near the occipital bone on the posterior part of the skull) belly. In other words, there is a muscle on the forehead (frontalis) and 1 on the dorsum of the caput (occipitalis), but there is no muscle beyond the acme of the head. Instead, the two bellies are continued by a wide tendon called theepicranial aponeurosis, or galea aponeurosis (galea = "apple"). The physicians originally studying human beefcake thought the skull looked like an apple tree.

The bulk of the face is composed of thebuccinator muscle, which compresses the cheek. This muscle allows you to whistle, blow, and suck; and it contributes to the action of chewing. In that location are several small facial muscles, ane of which is thecorrugator supercilii, which is the prime mover of the eyebrows. Place your finger on your eyebrows at the point of the bridge of the olfactory organ. Raise your eyebrows as if y'all were surprised and lower your eyebrows as if you were frowning. With these movements, y'all tin can feel the action of the corrugator supercilli. Additional muscles of facial expression are presented in Tabular array i.

| Table i. Muscles in Facial Expression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motility | Target | Target motion direction | Prime mover | Origin | Insertion |

| Brow | |||||

| Furrowing brow | Skin of the scalp | Inductive | Occipitofrontalis, frontal belly | Epicraneal aponeurosis | Underneath the skin of the forehead |

| Unfurrowing brow | Skin of the scalp | Posterior | Occipitofrontalis, occipital belly | Occipital bone; mastoid process (temporal os) | Epicraneal aponeurosis |

| Lowering eyebrows (e.one thousand., scowling, frowning | Skin underneath the eyebrows | Junior | Corrugator supercilii | Frontal bone | Peel underneath the eyebrow |

| Nose | |||||

| Flaring nostrils | Nasal cartilage (pushes nostrils open when cartilage is compressed) | Inferior compression; posterior compression | Nasalis | Maxilla | Nasal bone |

| Oral fissure | |||||

| Raising upper lip | Upper lip tissue | Elevation | Levator labii superioris | Maxilla | Underneath skin at the corners of the mouth; orbicularis oris |

| Lowering lower lip | Lower lip | Depression | Depressor labii inferioris | Mandible | Underneath peel of the lower lip |

| Opening oral cavity and sliding lower jaw left and right | Lower jaw | Depression, lateral | Depressor angulus oris | Mandible | Underneath peel at the corners of the oral cavity |

| Smiling | Corners of the mouth | Lateral top | Zygomaticus major | Zygomatic os | Underneath skin at the corners of the mouth (dimple area); orbicularis oris |

| Shaping of lips (as during speech) | Lips | Multiple | Orbicularis oris | Tissue surrounding the lips | Underneath skin at the corners of the oral fissure |

| Lateral movement of cheeks (e.m., sucking on a straw; as well used to compress air in mouth while blowing) | Cheeks | Lateral | Buccinator | Maxilla, mandible; sphenoid bone (via pterygomandibular raphae) | Orbicularis oris |

| Pursing of lips by straightening them laterally | Corners of the rima oris | Lateral | Risorius | Fascia of the parotid salivary gland | Underneath skin at the corners of the rima oris |

| Protrusion of lower lip (due east.g, pouting expression) | Lower lip and the skin of the mentum | Protraction | Mentalis | Mandible | Underneath skin of the chin |

| Raising upper lip | Upper lip | Meridian | Levator labii superioris | Maxilla | Underneath pare at the corners of the mouth; orbicularis oris |

Muscles That Move the Optics

The movement of the eyeball is under the control of theextrinsic eye muscles, which originate outside the heart and insert onto the outer surface of the white of the heart. These muscles are located inside the eye socket and cannot be seen on whatever role of the visible eyeball (Figure ii and Tabular array 2). If you have ever been to a doc who held up a finger and asked you to follow it upward, down, and to both sides, he or she is checking to make sure your center muscles are acting in a coordinated pattern.

Effigy 2. Muscles of the Eyes. (a) The extrinsic eye muscles originate outside of the middle on the skull. (b) Each musculus inserts onto the eyeball.

| Table 2. Muscles of the Eyes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Move | Target | Target movement management | Prime number mover | Origin | Insertion |

| Moves optics up and toward nose; rotates eyes from 1 o'clock to 3 o'clock | Eyeballs | Superior (elevates); medial (adducts) | Superior rectus | Common tendinous band (band attaches to optic foramen) | Superior surface of eyeball |

| Moves optics down and toward olfactory organ; rotates eyes from half-dozen o'clock to three o'clock | Eyeballs | Inferior (depresses) medial (adducts) | Inferior rectus | Common tendinous rind (band attaches to optic foramen) | Inferior surface of eyeball |

| Moves eyes away from nose | Eyeballs | Lateral (abducts) | Lateral rectus | Common tendinous ring (ring attaches to optic foramen) | Lateral surface of eyeball |

| Moves optics toward nose | Eyeballs | Medial (adducts) | Medial rectus | Common tendinous ring (ring attaches to optic foramen) | Medial surface of eyeball |

| Moves eyes up and away from nose; rotates eyeball from 12 o'clock to 9 o'clock | Eyeballs | Superior (elevates; lateral (abducts) | Inferior oblique | Flooring of orbit (maxilla) | Surface of eyeball between junior rectus and lateral rectus |

| Moves optics down and away from nose; rotates eyeball from 6 o'clock to nine o'clock | Eyeballs | Superior (elevates); lateral (abducts) | Superior oblique | Sphenoid bone | Surface of eyeball between superior rectus and lateral rectus |

| Opens optics | Upper eyelid | Superior (elevates) | Levator palpabrae superioris | Roof of orbit (sphenoid os) | Skin of upper eyelids |

| Closes eyelids | Eyelid skin | Compression along superior–inferior axis | Orbicularis oculi | Medial bones composing the orbit | Circumference of orbit |

Muscles That Movement the Lower Jaw

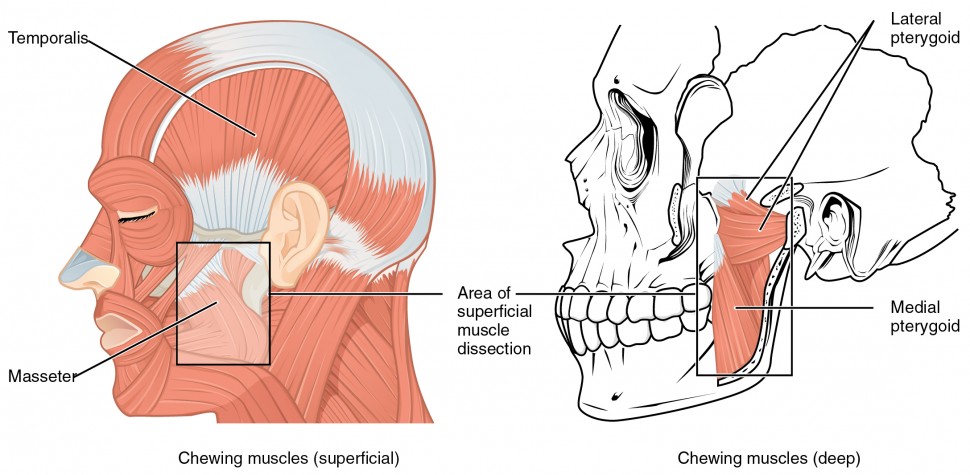

In anatomical terminology, chewing is calledmastication. Muscles involved in chewing must exist able to exert plenty pressure to seize with teeth through and then chew nutrient earlier information technology is swallowed (Figure 3 and Table three). The masseter musculus is the main muscle used for chewing because it elevates the mandible (lower jaw) to shut the mouth, and it is assisted past thetemporalis muscle, which retracts the mandible. You can experience the temporalis move past putting your fingers to your temple as you chew.

Figure iii. Muscles That Move the Lower Jaw. The muscles that move the lower jaw are typically located within the cheek and originate from processes in the skull. This provides the jaw muscles with the big amount of leverage needed for chewing.

| Tabular array 3. Muscles of the Lower Jaw | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Movement | Target | Target motion management | Prime mover | Origin | Insertion |

| Closes mouth; aids chewing | Mandible | Superior (elevates) | Masseter | Maxilla arch; zygomatic curvation (for master) | Mandible |

| Closes rima oris; pulls lower jaw in under upper jaw | Mandible | Superior (elevates); posterior (retracts) | Temporalis | Temporal bone | Mandible |

| Opens rima oris; pushes lower jaw out under upper jaw; moves lower jaw side-to-side | Mandible | Inferior (depresses); posterior (protracts); lateral (abducts); medial (adducts) | Lateral pterygoid | Pterygoid process of sphenoid bone | Mandible |

| Closes oral cavity; pushes lower jaw out under upper jaw; moves lower jaw side-to-side | Mandible | Superior (elevates); posterior (protracts); lateral (abducts); medial (adducts) | Medial pterygoid | Sphenoid os; maxilla | Mandible; temporo-mandibular joint |

Although the masseter and temporalis are responsible for elevating and endmost the jaw to suspension food into digestible pieces, themedial pterygoi andlateral pterygoid muscles provide assistance in chewing and moving food inside the mouth.

Muscles That Move the Tongue

Although the tongue is obviously important for tasting food, it is also necessary for mastication, deglutition (swallowing), and voice communication (Effigy four and Tabular array 4). Because it is then moveable, the tongue facilitates complex spoken language patterns and sounds.

Figure four. Muscles that Move the Tongue

| Table 4. Muscles for Tongue Movement, Swallowing, and Spoken language | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motion | Target | Target motion management | Prime mover | Origin | Insertion |

| Tongue | |||||

| Moves the tongue down; sticks tongue out of the mouth | Tongue | Inferior (depresses); anterior (protracts) | Genioglossus | Mandible | Tongue undersurface; hyoid os |

| Moves tongue up; retracts the tongue back into the mouth | Tongue | Superior (elevates); posterior (retracts) | Styloglossus | Temporal bone (styloid process) | Tongue undersurface and sides |

| Flattens tongue | Tongue | Junior (depresses) | Hyoglossus | Hyoid bone | Sides of natural language |

| Bulges tongue | Natural language | Superior (superlative) | Palatoglossus | Soft palate | Side of tongue |

| Swallowing and speaking | |||||

| Raises the hyoid bone in a way that likewise raises the larynx, allowing the epiglottis to cover the glottis during deglutition; also assists in opening the oral fissure by depressing the mandible | Hyoid bone; larynx | Superior (elevates) | Digastric | Mandible; temporal bone | Hyoid os |

| Raises and retracts the hyoid os in a way that elongates the oral fissure during deglutition | Hyoid bone | Superior (elevates); posterior (retracts) | Stylohyoid | Temporal bone (styloid procedure) | Hyoid bone |

| Raises the hyoid os in a manner that presses the tongue confronting the roof of the mouth, pushing nutrient back into the throat during deglutition | Hyoid bone | Superior (elevates) | Mylohyoid | Mandible | Hyoid bone; median raphe |

| Raises and moves the hyoid bone forrad, widening the pharynx during deglutition | Hyoid bone | Superior (elevates); anterior (protracts) | Geniohyoid | Mandible | Hyoid bone |

| Retracts the hyoid bone and moves it down during later phases of deglutition | Hyoid bone | Inferior (depresses); posterior (retracts) | Omohyoid | Scapula | Hyoid os |

| Depresses the hyoid bone during swallowing and speaking | Hyoid os | Junior (depresses) | Sternohyoid | Clavicle | Hyoid bone |

| Shrinks altitude between thyroid cartilage and the hyoid os, assuasive production of loftier-pitch vocalizations | Hyoid os; thyroid cartilage | Hyoid os: inferior (depresses); thyroid cartilage: superior (elevates) | Thyrohyoid | Thyroid cartilage | Hyoid bone |

| Depresses larynx, thyroid cartilage, and hyoid bone to create different vocal tones | Larynx; thyroid cartilage; hyoid bone | Junior (depresses) | Sternothyroid | Sternum | Thyroid cartilage |

| Rotates and tilts caput to the side and forward | Skull; cervical vertebrae | Individually: medial rotation; lateral flexion; bilaterally; anterior (flexes) | Sternocleidomastoid; semispinalis capitis | Sternum; clavicle | Temporal bone (mastoid process); occipital bone |

| Rotates and tilts the caput to the side and backwards | Skull; cervical vertebrae | Individually: lateral rotation; lateral flexion; bilaterally: anterior (flexes) | Splenius capitis; longissimus capitis | Sternum; clavicle | Temporal bone (mastoid process); occipital bone |

Natural language muscles can exist extrinsic or intrinsic. Extrinsic tongue muscles insert into the tongue from outside origins, and the intrinsic tongue muscles insert into the natural language from origins within it. The extrinsic muscles move the whole tongue in dissimilar directions, whereas the intrinsic muscles allow the natural language to change its shape (such equally, crimper the tongue in a loop or flattening it).

The extrinsic muscles all include the word root glossus (glossus = "tongue"), and the muscle names are derived from where the muscle originates. Thegenioglossus (genio = "mentum") originates on the mandible and allows the tongue to movement down and forward. Thestyloglossus originates on the styloid bone, and allows upwards and astern motion. Thepalatoglossus originates on the soft palate to elevate the back of the tongue, and thehyoglossus originates on the hyoid os to motion the tongue downward and flatten it.

Everyday Connections: Anesthesia and the Natural language Muscles

Before surgery, a patient must exist made gear up for full general anesthesia. The normal homeostatic controls of the body are put "on hold" and so that the patient tin can exist prepped for surgery. Control of respiration must be switched from the patient'south homeostatic command to the control of the anesthesiologist. The drugs used for anesthesia relax a majority of the body's muscles.

Amidst the muscles afflicted during full general anesthesia are those that are necessary for breathing and moving the tongue. Under anesthesia, the tongue tin relax and partially or fully cake the airway, and the muscles of respiration may not move the diaphragm or chest wall. To avoid possible complications, the safest procedure to use on a patient is called endotracheal intubation. Placing a tube into the trachea allows the doctors to maintain a patient's (open up) airway to the lungs and seal the airway off from the oropharynx. Post-surgery, the anesthesiologist gradually changes the mixture of the gases that go on the patient unconscious, and when the muscles of respiration brainstorm to function, the tube is removed. It all the same takes well-nigh xxx minutes for a patient to wake up, and for breathing muscles to regain command of respiration. Later surgery, most people have a sore or scratchy throat for a few days.

Muscles of the Anterior Cervix

The muscles of the anterior cervix assist in deglutition (swallowing) and speech by controlling the positions of the larynx (vocalism box), and the hyoid bone, a horseshoe-shaped bone that functions every bit a solid foundation on which the natural language can motion. The muscles of the neck are categorized co-ordinate to their position relative to the hyoid os (Figure 5).Suprahyoid muscles are superior to it, and the infrahyoid muscles are located inferiorly.

Figure 5. Muscles of the Anterior Neck. The anterior muscles of the neck facilitate swallowing and oral communication. The suprahyoid muscles originate from higher up the hyoid os in the chin region. The infrahyoid muscles originate beneath the hyoid bone in the lower cervix.

The suprahyoid muscles raise the hyoid os, the floor of the rima oris, and the larynx during deglutition. These include thedigastric musculus, which has anterior and posterior bellies that piece of work to elevate the hyoid bone and larynx when ane swallows; information technology also depresses the mandible. Thestylohyoid muscle moves the hyoid os posteriorly, elevating the larynx, and themylohyoid muscle lifts information technology and helps press the natural language to the top of the oral fissure. Thegeniohyoid depresses the mandible in addition to raising and pulling the hyoid bone anteriorly.

The strap-like infrahyoid muscles generally depress the hyoid bone and control the position of the larynx. Theomohyoid muscle, which has superior and inferior bellies, depresses the hyoid bone in conjunction with thesternohyoid andthyrohyoid muscles. The thyrohyoid muscle also elevates the larynx's thyroid cartilage, whereas thesternothyroid depresses it to create different tones of vocalisation.

Muscles That Movement the Head

The head, fastened to the top of the vertebral column, is balanced, moved, and rotated by the neck muscles (Table five). When these muscles human action unilaterally, the head rotates. When they contract bilaterally, the caput flexes or extends. The major muscle that laterally flexes and rotates the head is thesternocleidomastoid. In addition, both muscles working together are the flexors of the caput. Place your fingers on both sides of the neck and plough your caput to the left and to the right. You will feel the move originate in that location. This muscle divides the cervix into anterior and posterior triangles when viewed from the side (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Posterior and Lateral Views of the Cervix. The superficial and deep muscles of the neck are responsible for moving the head, cervical vertebrae, and scapulas.

| Table v. Muscles That Move the Head | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Movement | Target | Target motility direction | Prime mover | Origin | Insertion |

| Rotates and tilts head to the side; tilts head forward | Skull; vertebrae | Individually: rotates caput to opposite side; bilaterally: flexion | Sternocleidomastoid | Sternum; clavicle | Temporal bone (mastoid process); occipital bone |

| Rotates and tilts head backward | Skull; vertebrae | Individually: laterally flexes and rotates head to same side; bilaterally: extension | Semispinalis capitis | Transverse and articular processes of cervical and thoracic vertebra | Occipital bone |

| Rotates and tilts head to the side; tilts head backward | Skull; vertebrae | Individually: laterally flexes and rotates head to aforementioned side; bilaterally: extension | Splenius capitis | Spinous processes of cervical and thoracic vertebra | Temporal bone (mastoid procedure); occipital bone |

| Rotates and tilts head to the side; tilts head backward | Skull; vertebrae | Individually: laterally flexes and rotates head to same side; bilaterally: extension | Longissimus capitis | Transverse and articular processes of cervical and thoracic vertebra | Temporal bone (mastoid process) |

Muscles of the Posterior Cervix and the Dorsum

The posterior muscles of the neck are primarily concerned with head movements, like extension. The back muscles stabilize and motion the vertebral cavalcade, and are grouped according to the lengths and direction of the fascicles.

Thesplenius muscles originate at the midline and run laterally and superiorly to their insertions. From the sides and the dorsum of the cervix, thesplenius capitis inserts onto the head region, and thesplenius cervicis extends onto the cervical region. These muscles can extend the head, laterally flex information technology, and rotate information technology (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Muscles of the Neck and Dorsum. The large, complex muscles of the neck and back movement the head, shoulders, and vertebral column.

Theerector spinae group forms the bulk of the muscle mass of the back and information technology is the master extensor of the vertebral column. It controls flexion, lateral flexion, and rotation of the vertebral column, and maintains the lumbar bend. The erector spinae comprises the iliocostalis (laterally placed) grouping, the longissimus (intermediately placed) group, and the spinalis (medially placed) group.

The iliocostalis group includes theiliocostalis cervicis, associated with the cervical region; theiliocostalis thoracis, associated with the thoracic region; and theiliocostalis lumborum, associated with the lumbar region. The three muscles of the longissimus group are thelongissimus capitis, associated with the head region; the longissimus cervicis, associated with the cervical region; and thelongissimus thoracis, associated with the thoracic region. The 3rd group, thespinalis grouping, comprises thespinalis capitis (head region), thespinalis cervicis (cervical region), and thespinalis thoracis (thoracic region).

Thetransversospinales muscles run from the transverse processes to the spinous processes of the vertebrae. Like to the erector spinae muscles, the semispinalis muscles in this group are named for the areas of the torso with which they are associated. The semispinalis muscles include thesemispinalis capitis, the semispinalis cervicis, and thesemispinalis thoracis. Themultifidus muscle of the lumbar region helps extend and laterally flex the vertebral cavalcade.

Of import in the stabilization of the vertebral column is thesegmental musculus group, which includes the interspinales and intertransversarii muscles. These muscles bring together the spinous and transverse processes of each sequent vertebra. Finally, thescalene muscles work together to flex, laterally flex, and rotate the head. They also contribute to deep inhalation. The scalene muscles include theanterior scalene muscle (inductive to the middle scalene), theheart scalene musculus (the longest, intermediate betwixt the inductive and posterior scalenes), and the posterior scalene muscle (the smallest, posterior to the centre scalene).

Source: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/ap1/chapter/axial-muscles-of-the-head-neck-and-back/

Post a Comment for "Reviewing All the Muscles You Have Studied So Far Which Ones Allow You to Look Up at the Ceiling"